Tail Rotor

Contents

Tail Rotor¶

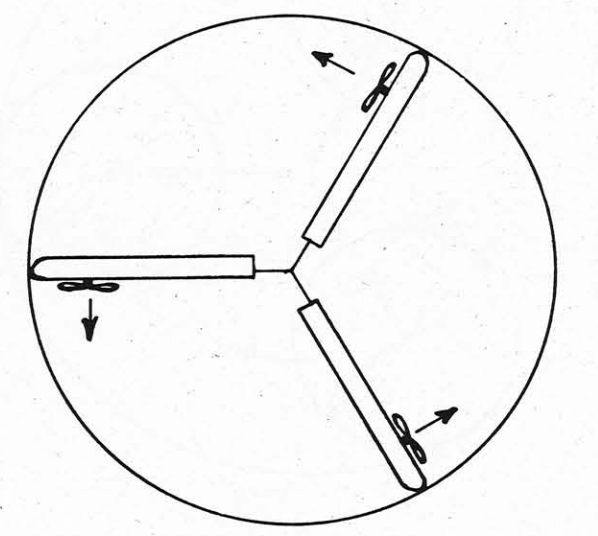

Quite simply, the reaction from rotating the main rotor (CCW, say) has the tendency to spin the rest of the helicopter in the opposite direction (CW). In forward flight, the vertical tail surface can be succesfully used to generate enough force (or moment about the helicopter CG) so as to counteract this (CW) moment. However, in hover or low speed flight a different mechanism is needed to balance the overall yaw moments for safe and sustained operation.

Conventional design UH60 helicopter [source])

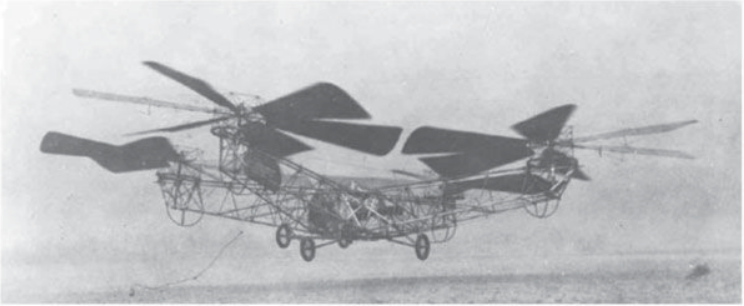

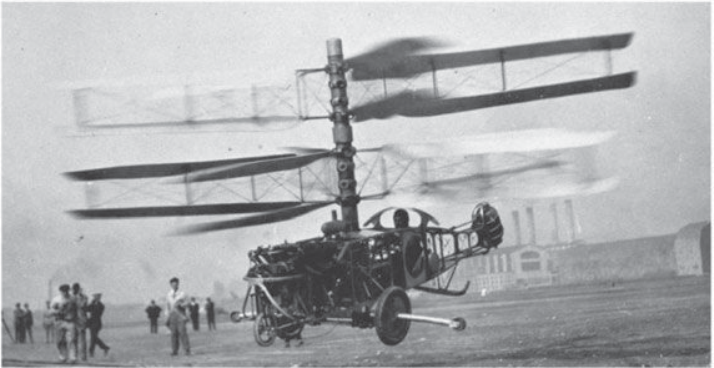

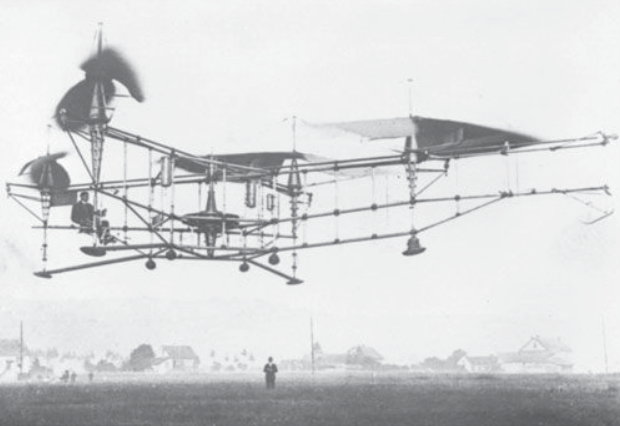

Early designs focussed on different multi-rotor configurations and some of these are shown below (refered to by the name of their inventor and the country). They were all experimental prototypes and were all abandoned because the configurations were mechanical too complex to be reliable for the technology at the time. Ultimately the main rotor + tail rotor design from Igor Sikorsky became the norm.

The initial resitance to the main rotor + tail rotor configuration is totally understandable, after all why should energy be expended separately just to balance the torque!? The tail rotor contributes nothing towards thrust generation in hover or forward flight in order to counter the drag and weight of the aircraft - unless canted, the tail rotor of the UH60 is canted by 20 deg which helps it to contribute to lift by about 181 kg [Pro09a]. The tail rotor of the experimental prototype RAH-66 was similarly canted.

Who needs a tail rotor!?¶

Alternate mechanisms or arrangments of rotors are possible in order to have trimmed rotorcraft flight. For e.g., instead of thrust generated using a tail-rotor, compressed air can be pushed out through slots over the tail boom and is referred to as the NOTAR (“no tail rotor”) concept. The Matra-Cantinieau “Bamby-Faon” was one of the early designs that implemented such a mechanism. Alternately, a propeller placed on one side of the rotorcraft can help achieve moment balance much like a tail rotor - see Fairey Gyrodyne figure below. The advantage here is that the thrust generated by the propeller can additionally assist the main rotor in forward flight.

In case there is no torque necessary to drive the rotor, i.e. the power needed to drive the rotor is obtained via alternate means, then the anti-torque mechanism can be entirely done away with. The Fairey Rotordyne was one such design where tip-jets provided the reactionary forces in order to turn the main rotor. In addition to assisting the rotor in forward flight, the pusher propellers on this design ensured controllability in all regimes of flight - yaw control in low-speed flight would be difficult, if not impossible, with just a main rotor driven by tip-jets and no tail rotor.

Surviving loss of tail rotor¶

Survivability or continued control of helicopter depends on

flight condition when loss happens

degree of damage/loss and helicopter design to cope with that loss

Loss at high speed

Large vertical stabilizers allow continued operation using a side slip

This has to be balanced with need for high speed sideward flight

issue in the Apache program [Pro09b](chapter 40)

Loss at low speed or hover

Autorotation1